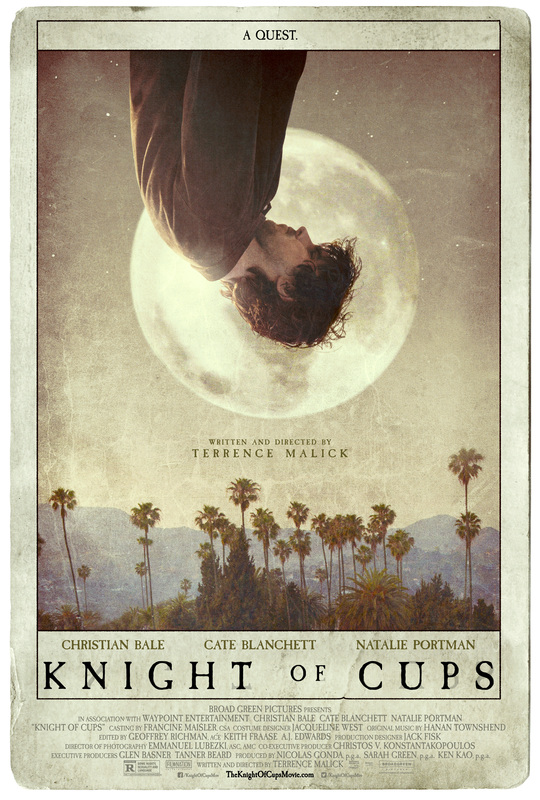

Rick moves in a daze through a strange and overwhelming dreamscape -- but can he wake up to the beauty, humanity and rhythms of life around him? The deeper he searches, the more the journey becomes his destination.

The seventh film from Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line, The Tree of Life), Knight of Cups (the title refers to the tarot card depicting a romantic adventurer guided by his emotions) offers both a vision of modern life and an intensely personal experience of memory, family, and love. Knight of Cups is produced by Nicolas Gonda, Sarah Green and Ken Kao. Prominent crew includes cinematographer Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki (Gravity, Birdman), production designer Jack Fisk, costume designer Jacqueline West, and composer Hanan Townshend (To The Wonder). The film’s ensemble cast also includes Antonio Banderas, Cherry Jones and Armin Mueller-Stahl.

The sensual dream of Terrence Malick’s new film, Knight of Cups, takes audiences on a ride that is all about the personal experience. The film unfolds through the innermost memories, desires and dreams of Rick, a successful writer who appears to have it all, but is nevertheless grappling intensely with the things we all grapple with: love, temptation, family, memory, meaning, faith, the way forward. Yet even as he struggles to find the right path, he discovers that the exploration itself – the readiness to take an open-minded, open-hearted trip through the awesome, mystifying fabric of life – might be more vital and exciting than the answers for which he yearns.

The film, shot by Malick’s longtime cinematographer, two-time Academy Award winner Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, offers a vision of pure cinema, in which an intermix of breathtaking visuals, raw emotions and rich symbolism transport the viewer into an intimate space of reflection, giving each viewer a uniquely individual, non-conventional journey and personal take on the story.

Since his first film, the stark, Midwestern crime drama Badlands, Malick has become renowned as the foremost poet of American cinema. In films that span from the World War II classic The Thin Red Line to his recent exploration of personal and cosmic time in The Tree of Life, Malick has worked with raw images the way an alchemist works with metals – bending and fusing them into an elixir of moods, states-of-mind and both the most transient and transcendent of feelings. Increasingly, he has moved beyond the constricted structure of conventional films – utilizing in-the-moment improvisation, untethered, roaming cameras, and bottomless emotional excavation to capture moments at their most genuinely and sometimes provocatively organic.

Rick yearns to restore a sense of enchantment – but his path is obstructed by a very modern tangle of family wounds, lifestyle temptations and that recognizable crossroads where high-tech illusions meet our most base and ancient desires. The twenty-first-century nature of the film’s journey struck a distinct nerve for each member of cast and crew.

Says Christian Bale, who portrays the lead role: “In Rick I find there is a sense of emptiness, a sense that he needs something, yet he doesn't know what the hell that thing is, which I think an awful lot of people can relate to right now. That feeling of emptiness strikes both people who are successful and who are not successful, both those who feel like they've achieved their dreams and those who are nowhere near achieving their dreams. None of us knows where we will find the answers to fill this emptiness. Rick is drawn to the beauty in the world, but beauty can either be a wonderful guide or a terrible distraction.”

Natalie Portman sums up Rick’s open-ended search for what will sustain him, which sweeps up her character in tumultuous events: “Amid the frivolity and excess and extravagance of Los Angeles, I see Rick as trying to regain his soul and confront the depths of his life.”

Producer Sarah Green sees Rick’s journey as that of a man trying to snap out of a state of sleepwalking. “In the beginning of the film, Rick is surrounded by beauty and he’s fascinated by it; but he isn’t able to go any further than the surface. He keeps missing the point until he has a moment of waking up ... then he falls asleep again ... then comes another awakening. And as soon as his gaze starts to go deeper, he starts to change. In my view, Rick is just beginning his life as the movie ends. I see all this potential opening in him.”

For Green, who has been working with Malick since The New World, Malick’s seventh film moves his cinematic expression forward yet again. “Terry, along with Chivo, his longtime cinematographer, have been changing cinematic language,” she observes. “They’ve forged a process and a style that allows movies to speak to us in a new way – and the more Terry and his team have refined their process, the further they are able to take it. It’s gotten to a point where you really can’t explain Terry’s movies in words. You simply have to experience them. It’s an experiential process making them and it is an equally experiential process for each person watching.”

Producer Nicolas Gonda, who first worked with Malick on The New World, was especially intrigued to see Rick’s journey progress through present-day Los Angeles – marking the first time Malick has set a film in the eponymous City of Angels. “It’s something he’s wanted to do for years,” notes Gonda. “Los Angeles has been part of Terry’s journey and, as such a keen observer of nature and human nature, he sets his sights on the city in his own way. You have some familiar elements: the parties, the beaches, the skyline. But his Los Angeles has infinite depth – it’s an onion that has countless layers and perspectives, and through this lens we’re able to see such an iconic city in ways we’ve never seen before.”

Gonda, too, believes the film won’t, and in a sense can’t, speak to any two people the same way. “We are all journeyers and adventurers in our own fashion,” he comments. “And I think what Terry’s films do for me and many others, by looking so deeply at the environments we move through, is remind us of the potential of the journey. Without ever giving a map to that point, or being didactic, his films help one explore the terrain and perhaps the direction you want to go in. This film is like a mirror -- everyone will see something different reflected back, and this is one of Terry’s great achievements. His films seem to speak to you wherever you are in your life or in this moment.”

For producer Ken Kao, Rick’s encounters with six decidely beautiful, but also complicated, lovers become his waypoints on the journey. “I believe this guantlet of women in Rick's life are almost like benchmarks, or milestones, of who Rick is and how he's developing as a person,” Kao describes. “Of course, it’s always seductive to think another person will give you the easy answer to what's missing in you, but Rick comes to see that isn’t exactly what he’s looking for.”

Kao also sees the film as giving filmgoers a rich alternative to the typical two hours of passive viewing at the movies. “I think this is the next evolution of Terry's filmmaking,” he states. “Knight of Cups is bolder, edgier and has his most contemporary setting. There are a lot of things different from Terry’s previous films, but like all his films, you cannot turn off your mind. For those looking for a different kind of film, be prepared to have a truly personal experience.”

Rick’s Quest

Taking the role of Rick is Christian Bale in an inward-focused departure from his acclaimed roles in such films as The Fighter, for which he won an Academy Award, and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy, in which he reawoke the legend of Batman in a more complex and human form. Knight of Cups marks his second collaboration with Terrence Malick, having portrayed the early American settler John Rolfe a decade ago in The New World.

For producer Ken Kao, a reunion between the two was intriguing. “Christian obviously is an incredible actor – but also, since he and Terry have a long-standing, personal relationship, they started off with a comfort with each other.”

Bale’s intricate journey into uncovering Rick began via conversations with Malick. “Terry initially gave me a lot of his thoughts on the character and his relationship to the different people in his life, especially his family and the various women who influence him, so that I would have all that background in my head. But after that, he invited me to just see what happened,” Bale recalls.

This spontaneous form of film acting – the philosophical antithesis of line-reading – is something Malick has been exploring for some years. Explains Bale: “The philosophy behind it is that Terry wants you to jump in before you’re actually what an actor would consider ready in a conventional way – because Terry feels that by the time you feel ready, by definition you're already trying too hard and it’s no longer authentic. So by contrast, he wants his actors to come to each scene with a lack of knowledge as to what might happen, and without a predetermined goal. That way you truly see what evolves naturally between the characters.”

Although he started with only bits and pieces of Rick’s persona, over time, Bale began to get a richer and deeper view of Rick. He sees him as “a man of words, yet one who has lost his way with expression. Rick has achieved everything that he once imagined would make him feel fulfilled and successful, but in approaching that mountaintop of success, he wonders...what is beyond it?”

Bale continues: “Rick is asking himself the question: is this really who I am? I see him as a lost character trying to rediscover something perhaps he knew about himself when he was younger. He’s trying to figure out: Am I a good or a bad man? Could I have done things differently?”

Malick’s quaky, sun-baked Los Angeles, which both alienates and speaks to Rick, especially intrigued Bale. “Los Angeles is often portrayed as a vacuous, soulless town,” the actor observes. “There are elements of that in the film in the parties Rick goes to – but there is another Los Angeles you see where Rick rediscovers sincere, genuine people. You see how vast and full of different people the city is. I don’t take the film as a critique of L.A.; I see it as more a celebration of the city and its possiblities.”

Bale acknowledges that different people are likely to bring back quite different understandings of Knight of Cups and latch onto it in different places where it connects with their own trials and quests. That is also part of the beauty of it, he says.

“Because Terry does not tell you how you should be feeling, that allows for a great deal of personal interpretation. To me it’s similar to a song that two people might sing the same way, yet it has two very different meanings to them. That's how I see Knight of Cups; two people might sit next to each other in the same audience, but their experiences won’t be the same,” Bale concludes.

Production designer Jack Fisk echoes Bale’s comparison, likening Knight of Cups to the experience of viewing a resonant painting. “When you go to a gallery and see a painting, you bring your own thoughts and history to what you are seeing,” Fisk reflects. “If I see the same painting as another person, it affects me completely differently than that other person because you complete the painting with all that you bring to it. I think that’s the same way this movie works – you’re completing the film when you see it, and that’s the way I look at a lot of Terry’s work.”

The Women

Surrounding Rick in Knight of Cups is a circle of women who entice, inspire and provoke him – and form a kind of ode to the power of the feminine to spur change. Malick assembled an ensemble of extraordinary actresses to portray them, including Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman, Freida Pinto, Teresa Palmer, Imogen Poots and Isabel Lucas.

At the center of the circle is Rick’s regret-filled ex wife, Nancy, a fiercely intelligent yet compassionate doctor who feels she was unable to help Rick stay on a path that would have saved their unraveling marriage. Everyone involved in the project was thrilled to watch Blanchett – a two-time Oscar winner for The Aviator and Blue Jasmine and a seven-time nominee including recently for Carol – embody the woman who illuminates Rick’s heartbreak. Says Sarah Green: “Cate is an amazing force of nature herself and she brings such gravitas, depth and complexity to Nancy.”

Having watched every film Malick had made to date, some multiple times, Natalie Portman was thrilled to have her first chance to work with the director. “Terry has a unique capacity to marry image and sound into great emotion,” she observes. “You see new things every time you see one of his films. They have rhythms that create emotional echoes and each one is an amazing experience.”

Malick sent Portman a contrasting array of books to help her not so much get into character as to explore themes related to the film: the Russian literary master Mikhail Lermentov’s A Hero of Our Times, about a fatalistic casanova’s adventures in 1820s Russian society; artist Vincent Van Gogh’s searching letters to his brother Theo; George Eliot’s Victorian satire Daniel Deronda, about English aristocrats’ search for meaningful lives; and Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard, an account of the author’s trek into the Himalaya and a meditation on beauty, suffering and inner calm.

Portman describes her own character, a married woman having an affair with Rick that unravels, as going through “a whole range of lust and abandon in an illicit relationship that has many consequences.” She adds: “I think our situation reminds Rick that there are some sins you can’t take back, some injuries that you cause from which you can’t heal, and some actions that can be irreparable.”

She says she connected immediately with Bale, which freed up her instincts. “Christian is so amazing. Due to the nature of his character, he was sort of the host of the movie, welcoming different people into his world, then moving on to the next guest,” Portman point outs. “He made me feel at ease immediately so we could jump right into these very emotional, intimate moments that might be scary otherwise. He’s so spontaneous and fun, it was easy to be playful, wild and extreme with him.”

Throughout her scenes, Portman recalls that Malick kept her in a constant state of wonder and surprise, but one thing about him stood out. “I think the most surprising thing to me was just how much fun Terry aims to have,” she notes. “His films can be quite serious so it was wonderful to also see the looseness, the flow, the sense of curiosity and the willingness to try new things. A film like this is a leap of faith, but I always felt in very safe hands, because I know his intentions are so pure.”

For Freida Pinto, who plays the model Helen, entering Malick’s filmmaking realm was like “an out-of-body experience,” she reports. The actress, who came to the fore in Slumdog Millionaire and has gone on to a diverse career, says she has never worked this way before, off script and off any marked path. She explains: “There were lines Terry would send in, but they were more of a guide, not a script – a guide to help you open yourself up to go into a stream of consciousness. Many times what would happen is Terry and I would start having a conversation about anything and everything and before I knew it, the camera was rolling. It was all very organic and never pre-planned. It’s quite a different experience and requires you to let go of so much.”

Pinto notes that among Rick’s sextet of women, her character Helen is unique. “What I understood from Terry is that Helen represents to Rick a whole different world that he’s not familiar with, a world that baffles him. She is probably the only woman that he does not go to bed with, because she has a quality like a bird. Every time he gets close to her, she flies away.”

She drew on her personal interests in yoga and meditation to frame her character. “I wanted her to have a very strong center, where she’s really not affected by the outside world. She breathes through it all to combat it – and that’s the lesson that maybe she gives Rick,” says Pinto.

Working with Bale brought that all to vibrant life. “Christian’s so down to earth, but he’s also super-flexible,” she observes. “I think that’s what truly makes someone a great actor – when they’re willing to give as much as they get.”

Rising Australian star Teresa Palmer notes that she was thrown into her first scene with Bale as the Vegas striptease artist Karen without any introduction – and Bale thought she was a real club dancer Malick hired. “I arrived with this elaborate backstory for my character and, thinking I was improvising with Christian, I told him I was a dancer and had a daughter, Melanie. And he didn’t realize until he saw a poster for my film Warm Bodies that I was actually an actor,” she laughs.

Palmer did work with experienced strippers to learn how to move her body. “What I learned from them was to never stop moving, just constantly keep your body rolling, even when you’re connecting with someone, keep moving. In my scenes with Christian, if I’d get caught up in ad-libbing, I would hear them in the background saying ‘keep moving, keep moving.’”

Her performance is physical, but Palmer also brought her own inner essence to the role. “I think Rick really enjoys Karen’s freedom, so I just gave myself over to that,” she describes. “I essentially played a more heightened version of myself, a bit louder, a little crazier, a little freer.”

In another scene, Palmer was sent into the Pacific Ocean with Bale and a GoPro camera. “It blew my mind to be in the ocean with Batman, filming ourselves for a Terrence Malick movie,” she says. Yet, those kinds of experiences opened her eyes to a more vital way of working. “I may have been ruined for the rest of my career because now I want to make every single film like this,” Palmer laughs. “Most of all, it reinvigorated my passion for the craft.”

As the defiant Della, English actress Imogen Poots was similarly smitten with the film’s style. “I was excited to go into this job knowing it was not going to be conventional and that the process itself was notoriously abstract. I saw it as a sort of a vacation from the industry and its constraints,” she muses.

Like her castmates, Poots received only snippets from Malick about her character, but they were snippets that resonated deeply. “Terry said ‘she’s from everywhere and nowhere. She’s like smoke,’” recalls the actress. “From those notes I had to explore: what does she represent? As I began to understand Terry’s interest in archetype, I started to see what Della contributes to the story as a whole. I was able to move forward that way, having no expectations, but being curious and open to it.”

That also meant letting all preconceptions of moviemaking fall away. “I felt like it was almost a re-introduction to working with a camera,” Poots comments. “Terry and Chivo use a kind of balletic choreography that doesn’t exist outside their filmmaking.”

Playing the transformative character who is also named Isabel, Isabel Lucas found that Malick’s in-the-moment process led to learning all over again how to approach a character. “I had nearly a year knowing that I had the part, and I really wanted to do everything and anything I could to prepare, yet there was nothing I could do,” she reflects. “Instead, it becomes about learning to really listen and discover moments and being very present. That was both really freeing and a bit scary.”

Lucas says Malick dissolved her fear by creating such a warm, open set. “There was quite a magical feeling,” she describes. “Terry instills trust in everyone because he trusts you so much. You really would do anything he asks because he’s so full of good intentions, and you feel that.”

She goes on: “The way Terry works, things become clearer as you go. It parallels life in a way. You can’t force things in life. Life happens and you choose to trust it. Terry works in a similar way. He puts various essences together and then he lets them unfold in a way that is natural and unpredictable.”

Her own character is hard to pin down – and that was intentional, says Lucas. “I feel like Isabel is a memory, perhaps from Rick’s childhood. To me, she’s like his conscience, or a guardian angel of a sort. She’s that voice that too often gets drowned out by the world...one we don’t always listen to. Rick is so distracted by the material world that he’s become quite disconnected. He exists too much in his head, too much in his ego, and my character reminds him of his soul again.”

The character moved Lucas. “Her words are so beautiful, I had trouble not crying when I was reading them. I said to Terry, ‘I recognize that voice. We all have that voice in us and you can choose to be aligned with it, or you can do the opposite.’ That’s when it clicked for me,” she remembers.

Working with Bale under these very specific conditions – where neither knew what the other was about to do – was intriguing. “Christian went into it not knowing what to expect from our relationship, so we both had to roll with it and see what would be revealed,” Lucas explains.

That organic beauty came out in one of Lucas’s favorite spontaneous unfoldings in the film. “I love the scene where you have these incredible silhouette shots of me and Christian walking among the desert windmills and suddenly we end up dancing under a full moon with this incredible camerawork. It felt really wild and peaceful and there was such great energy,” she concludes.

The Family

While he is surrounded by women, Rick’s story is also a father-son story. For if his future is currently uncertain, Rick’s past, like so many, is a stony weight around his neck that he has been trying to cut free. In the wake of his younger brother’s death years before, he is still grappling with a hard- edged, volatile dad and a second, troubled brother.

Playing Rick’s brother Barry is Wes Bentley, whose roles have spanned from American Beauty to The Hunger Games and Interstellar.

Like others, Bentley found himself enamored with the way Malick gives his actors shards of thoughts and emotions to wrestle with in the moment. “Terry only gives you a feel for your character and then he lets you go -- just like his films give you a feel for the life that is happening in front of you. He aims to catch that rare intersection where you get a glimpse into how life really is.”

One thing Bentley did know is that Barry’s life has turned out very different from Rick’s – yet they share in common the same loop of struggle with their father and grief over their brother. “Rick and I had a tough upbringing so I think we both feel in conflict with our father. But while Rick went off to Los Angeles, Barry’s the one who stayed behind and dealt with the family. As he says, he ‘lived in the fire of the house’ and it has made them very different people. Barry has struggled with drugs and alcohol and is just coming out of that, looking for a fresh start,” Bentley describes.

Bentley sees his character as bringing out one of Knight of Cups’ most resonant themes. “To me, the film is a lot about how family shapes you. Rick is trying to find himself but he’s also trying to understand his roots, to understand these people he can’t ever escape. No matter where you go you can’t get away from your family – but maybe that’s not such a bad thing,” he offers.

Having the chance to work on such a subterranean emotional level with Bale gratified Bentley. “I’ve been inspired by Christian since I was a kid,” Bentley says. “He’s inspired me with his role choices but also in his commitment to subtlety – I think Christian is one of the subtlest actors of our generation. He also is just a great guy to work with. It’s so important to have sense of humor on set and Christian has an amazing sense of humor. It was really fantastic to find out all these wonderful things about him after being such an admirer of his work.”

Yet once the camera was on, the rapport instantly amped up in intensity. “When the camera was off we were both like little kids trying to make each other laugh – but as soon as the camera was following us, we were each trying to find some way to break the other one,” Bentley summarizes.

Producer Sarah Green notes that Malick expanded the role of Barry around Bentley’s performance. “Wes and Christian had such a wonderful rapport and built something so amazing together that Terry kept asking Wes back. The scenes with Barry are a great way of getting beneath Rick’s skin. He and Christian and Brian Dennehy are all such great actors, you could throw any situation at them and they would go deep. It was very moving to watch,” Green says.

Rick and Barry’s heartbroken father is portrayed by screen, television and stage veteran Brian Dennehy, who works for the first time with Malick. He says it was impossible to resist the chance to collaborate with a cinematic visionary who has the audacity to follow his own drumbeat in these times. “Everybody signs on to work with Terry because who else is out there who does this now?” Dennehy asks. “I had a great time on this film. Everybody was so anxious to help Terry realize his vision. It’s a very special situation which is why there is no way you can turn it down.”

It wasn’t an easy role, as Rick’s father is one of the film’s most conflicted, bedeviled characters, a man who was tough on his children and must abide the consequences. “Rick and Barry are caught in that generation gap between father and sons,” Dennehy observes. “I think my character is a product of his generation, of his upbringing. He’s someone who was brought up to believe you lived a certain way, with certain responsibilities and that is the way he knew to be a father.”

Producer Ken Kao says of Dennehy: “On a deeper level, Brian represents this father figure Rick felt he could never satisfy. It plays a role in why he feels so aimless inside.”

The role brought Dennehy not only into emotional confrontation but physical confrontation with Bale. “Christian is a very physically strong man – he threw me around that set like I was a toy,” Dennehy laughs. “Of course I’m in terrible shape now; 50 years ago I would have kicked his ass. But truly, he’s a terrific guy to work with. He’s got a great sense of humor and he’s a real person.”

Dennehy goes further: “Christian’s energy isn’t an exterior energy; it’s all inside. It comes out of his eyes, out of the way he holds himself. And he has an impact. When he walks into the set, he has a certain physical impact, that star quality. It’s very effective for a character like Rick.”

Christian Bale stars as ‘Rick’ in Terrence Malick's drama KNIGHT OF CUPS, a Broad Green Pictures release.

Christian Bale stars as ‘Rick’ in Terrence Malick's drama KNIGHT OF CUPS, a Broad Green Pictures release. A New View of Los Angeles

Every Terrence Malick film offers a rich, symbolic visual palette to explore – and Knight of Cups goes as far as ever into visual delights, puzzles and images that burn themselves into the back of one’s brain. The visuals were borne not just out of Malick’s imagination but from the very specific synergy of Malick and his DP, Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, known for his immersive, kinetic and spontaneous camera style.

“Terry and Chivo share three characteristics that form a bond between them: very open minds, a great sense of discipline and a terrific sense of humor,” observes producer Nicolas Gonda. “When they’re around each other it’s like a chemical reaction that keeps regenerating. They’re always coming up with ideas, and ideas for how to achieve those ideas. They’re two of the most technically astute people I’ve ever met in any walk of life – and yet they also are dedicated to exploring the essence of art.”

On this film, Malick and Lubezki dipped into a vast toolbox, using technologies high and low, from 35mm filmstock and wide-angle lenses to wrist-strap GoPro cameras in the hands of the cast, to the tiny, disposable Japanese cult digital camera Harinezumi, known for its dreamlike images.

A consecutive Oscar winner for Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, Lubezki had garnered nominations for Malick’s The Tree of Life and The New World. Knight of Cups would be the first time the duo tackled the environs of twenty-first-century Los Angeles – an earthquake-rattled land at once hallucinatory and stark.

“When we started talking about how Chivo and Terry were going to shoot L.A., it was very exciting,” recalls Ken Kao. “Los Angeles is, in a lot of ways, its own character in the film.”

Adds Sarah Green: “Los Angeles is known for being the place where dreams may, or may not, come true; it feeds into this story of someone living in a surface world. The city gave us a powerful backdrop to emphasize a character losing track of himself amid the most enticing distractions.”

Freida Pinto felt a similar synergy between Malick and the setting. “Terry has done such a great job of balancing the debauchery and excess with the grounding beauty and soul-searching that can happen in a place like L.A.,” she describes. “He finds both the frenzy and the stillness.”

Imogen Poots was taken aback by the richness of Malick’s Los Angeles. “Terry and Chivo captured a side of the city which is quite exquisite. It’s the electronic side of Los Angeles. It’s very alive and full of myth. You feel the time rolling by and the heat beating down and a sense of extensive nothingness at times,” she says. “There’s so much there.”

Like California itself, Knight of Cups is drenched with aquatic imagery, ranging from Christian Bale diving with a GoPro to second unit director Paul Atkins setting up complex underwater sequences on the floor of a swimming pool. This liquid realm also reflects back on the tarot card figure of the Knight of Cups – who is said to combine fire and water, trying to find a balance to the most passionate and serene elements of life.

Malick is known for shooting miles of footage – never stopping the camera until the light runs out – and this film was no different. But the director’s process was more immediate than ever. “Terry has an incredible ability to pinpoint the most honest moments and hone in on them,” says Green. “The result is a beautiful, unexpected combination of the planned and the unplanned, the intentional and the accidental. He and Chivo trust each other so deeply now they can be very bold.”

The mix of cameras added to the fun. Says Kao, “No matter how celebrated they are, Chivo and Terry are always looking to push the limits again, to find the next step of evolution. Chivo was really excited about using different mediums in this film. We shot on film, we shot on digital, we played with GoPro cameras, and we used a tremendous variety of lenses and housings.”

Adds Gonda, “Giving the GoPro to members of the cast and crew enabled Chivo and Terry to be surprised by what images came back because the GoPro essentially creates a cinematographer out of anybody. That element of discovery really excites and inspires them.”

For the actors, working with Chivo’s freewheeling, go-anywhere cameras and without a script – essentially without a net – offered an electrifying challenge. “The actors certainly had to be quick on their feet,” observes Kao. “The operative word was ‘adaptable.’ You had to be ready for anything.”

Natalie Portman was thrilled to tango with Lubezki’s darting camera. “Chivo is a master and to be able to shoot in natural light with all these different cameras the way he does is incredible,” says Portman. “You often feel the camera is in the scene with you and you’re dancing with it.”

“Watching the process from the outside was also a thrill,” says Imogen Poots. “From afar, the camera crew looks almost like a kind of creature,” Poots observes. “They’re moving in unison while people are sprinting to pick up equipment, and it’s like a performance art piece.”

Christian Bale observes that not knowing where the camera will be allows an actor to take the camera completely out of his consciousness – triggering unadulterated responses. “It makes things very natural,” he explains, “because even when the camera is on you, you know that it might leave you at any second, so you simply get on with things and start to ignore whether the camera's watching you or not.”

Isabel Lucas felt similarly: “The camera is a witness. Sometimes it comes so near you’re accidently bumped by it, but you get used to it and you open up to it. It’s like the camera becomes your friend that is a machine – that's something Christian said, which is a cool way to think of it.”

For Teresa Palmer, the process shares a kinship with live theatre. “It’s almost like doing a play, because you’re always on and the camera just finds you at times,” she elucidates.

But this required the actors to shift their own perceptions, never an easy proposition. “After years of doing things one way, a certain conditioning happens,” explains Wes Bentley, “in the way you normally play to the camera. So a lot of the effort you have to make with Terry and Chivo is shedding that conditioning. You learn to trust that the camera will land on your best moments.”

Gonda observes that Malick builds this trust through deep personal connection. “Terry has a remarkable ability to communicate with people and to cater his communication specifically to the type of person you are. Conversations with him are wide-ranging – they evoke art, music, a whole host of references. So even though this film had no traditional script, there was this very bespoke form of communication giving the cast and crew more than what they could ever get from the page.”

Cast member Thomas Lennon, who cameos as a Hollywood partygoer, notes that working with Malick had the quality at times of waltzing into a looking-glass world of dreams. “It’s that dream where you’re with Christian Bale and Terrence Malick ... and Terrence Malick hands you a piece of paper with a line that says, ‘there's no such thing as a fire proof wall’ and you have to figure out what to do! And that’s really how my day on the set started,” he recalls with amusement. “Later, I realized this wasn't as crazy and chaotic as it seemed, because it leads to something very honest.”

Indeed, Gonda emphasizes that a vast amount of carefully-plotted strategizing goes into allowing Malick’s on-set creative freedom to blossom. “Terry creates a remarkable environment where cast and crew can explore in natural, un-premeditated ways – but this is only made possible through an extraordinary amount of meticulous pre-planning,” the producer explains.

The planning process on Knight of Cups was bolstered by a tight-knit group of collaborators, including Chivo, production designer Jack Fisk and costume designer Jacqueline West. Their familiarity with Malick’s approach and aesthetic brought a seamlessness to the spontaneity.

“This trio first came together on The New World and they’ve kept coming back as Terry’s core team,” notes Green. “It’s a close family and a well-oiled machine at the same time. We’re able to keep very lean and move quickly, which in turn gives Terry maximum freedom.”

Jack Fisk has been working with Malick since the very start of the filmmaker’s career and has developed an energizing creative relationship with him. “Terry has been a great friend and a great teacher. He’s like a brother to me and I treasure every time I get to work with him,” says Fisk.

He notes that this relationship differs from that with any other director, though he has worked repeatedly with many auteurs. “Terry has always spoken more about characters and ideas than about physical things. I don’t know that I’ve ever talked to him much at all about sets,” Fisk relates. “We talk about many other things related to the film instead. In a sense, he’s like a jazz musician. He plays a note and the rest of us start riffing on it – Jacqui with the costumes, me with the sets.”

On Knight of Cups, the fusion of Malick and Los Angeles was especially exciting for Fisk, who previously designed David Lynch’s neo-noir Mulholland Drive, a very different vision of the city. “Los Angeles has probably been shot more than any other city but Terry has a new viewpoint,” observes Fisk. “For me it’s a showy, cold Los Angeles, with lots of empty spaces. We also shot a lot by the ocean. I think for Terry the sea is very important, in that we all come from the sea and it’s like a humble beginning, even while the city is focused on fame and fortune.”

The tortuous sprawl of Los Angeles with its swirling, Mobius strip of freeways and extremes of desperation and debauchery makes it nearly impossible to capture the whole city en masse – but Fisk was excited that that Malick wanted to let the kaleidoscopic nature of the metropolis take the lead in his film.

“There are usually so many rules to shooting in L.A. – but Terry loves the idea of shooting guerrilla-style, so we put everyone in little vans and it was almost like a commando production. We would just pop into a neighborhood without even looking like a film crew and we shot so much footage it’s almost like a collage of the city,” Fisk explains. “At times complete locations were used just for fragments – the corner of a door here or a plant there. But I think the resulting feeling is that the film becomes an expressionist painting, an expressionist Los Angeles that you’ve never seen.”

Fisk was taken aback when he saw the finished film. “It made me think about my life, about my relationships and it made me think about where I want my mind to be. I’ve thought about it probably more than any other film I’ve seen,” he sums up.

For West, who most recently received an Oscar nomination for her design of the early Western apparel of The Revenant, working with Malick is always reinvigorating. “Terry’s an almost metaphysical director,” she comments. “He truly works from an almost visceral reaction to things, so I try to work the same way with him. I try to figure out the feeling he wants to give people. Terry always says I’m clairvoyant because I seem to know what he wants; but it’s from having worked with him so closely.”

Early on, West and Malick established Rick’s look: sleek, dark, almost anonymous suits befitting a current-day knight of California. “The dark suit and dark shirt create a frame so that Christian’s face almost glows on the screen and you’re left undistracted from the emotions and feelings you see there,” says West. “Rick starts out a dark character, though he’s looking for light, so the darkness suits him. You also get a wonderful contrast of this dark figure moving against the whitewash of Los Angeles, which is something Terry wanted.”

For the women circling Rick, West explored variations-on-a-theme of diaphanous, flowing fabrics. “Each woman is fashionable in her own quirky way,” says West. “I dressed them according to the moods of their scenes, and in terms of what they are showing Rick, whether it is honesty, spirituality or another concept. I see the women as a kind of prism, refracting light onto Rick.”

The biggest costume challenge of the film came via the eye-popping celebrity dog party thrown by Tonio, played by Antonio Banderas, for which West even designed a series of glam canine suits and sweaters. She especially enjoyed exploring the edges of fashion for the human side of things. “Terry wanted it to be very, very high fashion and because it’s a Terrence Malick movie, you can rely on the generosity of strangers, so a lot of designers loaned me pieces to make this over-the-moon, uber-classy, high-end runway party.”

At times, West recalls, the clothing faced peril. She relates: “Antonio Banderas brought his own beautiful Armani tux – and then Terry sent him into the swimming pool in it! But Terry is such a divining rod that wherever there’s water, someone goes in.”

Later, the film’s symphonic visuals were entwined with the equally wide-ranging sounds of young, Austin-based composer Hanan Townshend’s score. “Because the film has this mystic quality, fusing contemporary L.A. with a sense of fable, we needed an original yet sweeping score,” says Ken Kao. “Hanan’s score is an integral part of the momentum that moves Rick through his journey.”

That journey is something that largely stands apart in the current cinema – a journey designed to take every viewer somewhere unique, a journey that takes a sharp left turn from the three-act view of the world we expect as it pursues a deeper source of enchantment in the experience of life itself.

Ken Kao offers advice for how to approach it: “If you allow the film to kind of wash over you, and stay aware to whatever feelings that surface, it becomes a very self-reflective experience. That’s why everyone is so excited to work with Terry.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed